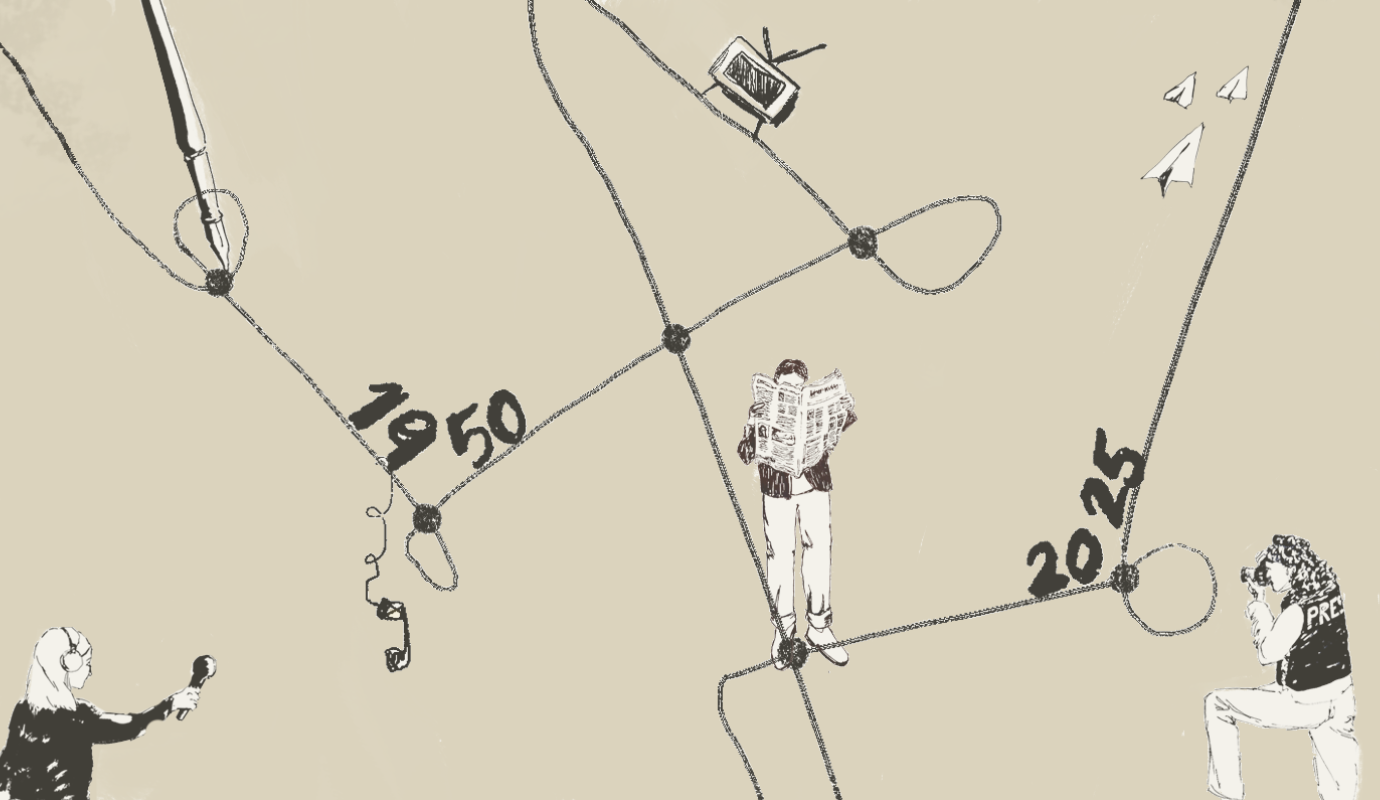

IPI 75: Solidarity, innovation, resilience

An IPI archive online exhibition

Introduction

When journalists can work freely, society can hold power to account, expose wrongdoing, and share stories that shape our world. When the media is silenced, we all lose the right to make informed choices.

For 75 years, the International Press Institute (IPI) has defended these freedoms.

Through wars, censorship, revolutions, and technological upheavals, journalists have shown resilience — adapting with solidarity, creativity, and innovation.

This exhibition draws on IPI’s rich analogue archive documenting the global struggle for a free press.

It reminds us that democracy and press freedom are never guaranteed. They must be protected, renewed, and passed on to future generations.

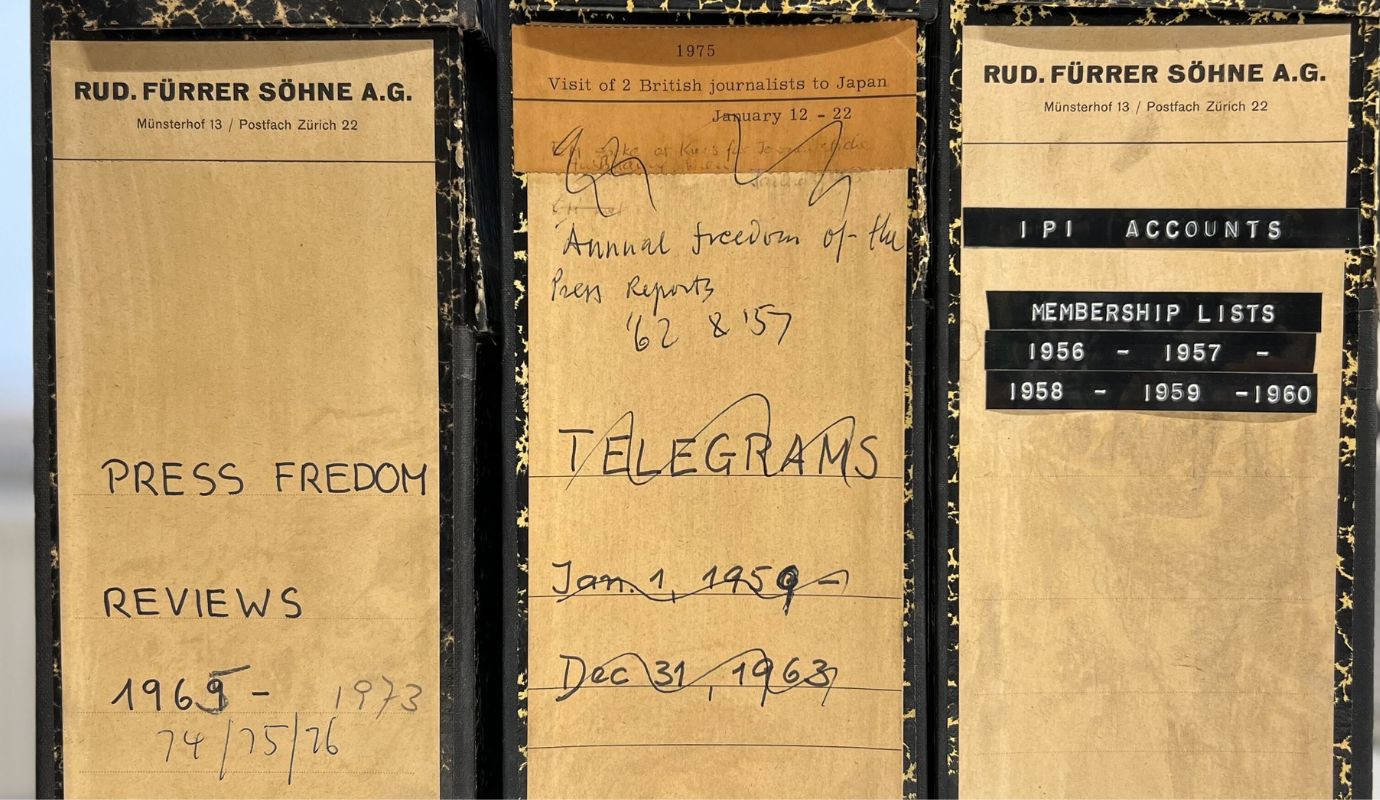

Housed in rows of boxes lining the shelves of the Press Freedom Room at IPI’s headquarters in downtown Vienna, our archive holds 75 years of history: thousands of pages of publications, research, correspondence, World Congress records, and the flagship IPI Report (1952-2005).

Together, these materials form a unique documentary record of the global struggle for press freedom — the consistent and creative work that IPI members have carried out across seven decades and around the world.

Our goal is to digitize and modernize the archive so it can serve as a premier digital resource for media historians and researchers.

Follow our thematic sections: turning points, resisting censorship and attempts to undermine the flow of news, and the dynamics of technological change.

• TURNING POINTS

The first turning point was the era of post-war reconstruction and reconciliation from which IPI arose. It was a time of optimism, yet also of profound challenges to peace.

In the aftermath of World War II, global efforts to defend media freedom had to respond rapidly and imaginatively to the onset of the Cold War, the collapse of major empires, the need to develop specialist forms of professional journalism, and the obstacles facing post-colonial and post-dictatorial societies.

It was out of this fraught but hopeful context that IPI was founded in 1950 as a pioneering attempt to meet these demands and to anchor press freedom in a changing world.

International Press Institute Exploratory Conference, New York, October 1950

International Press Institute Exploratory Conference, New York, October 1950

Everyone joins IPI for the sake of an idea... All can work for the improvement of understanding among peoples and against the poisoning of international relations.

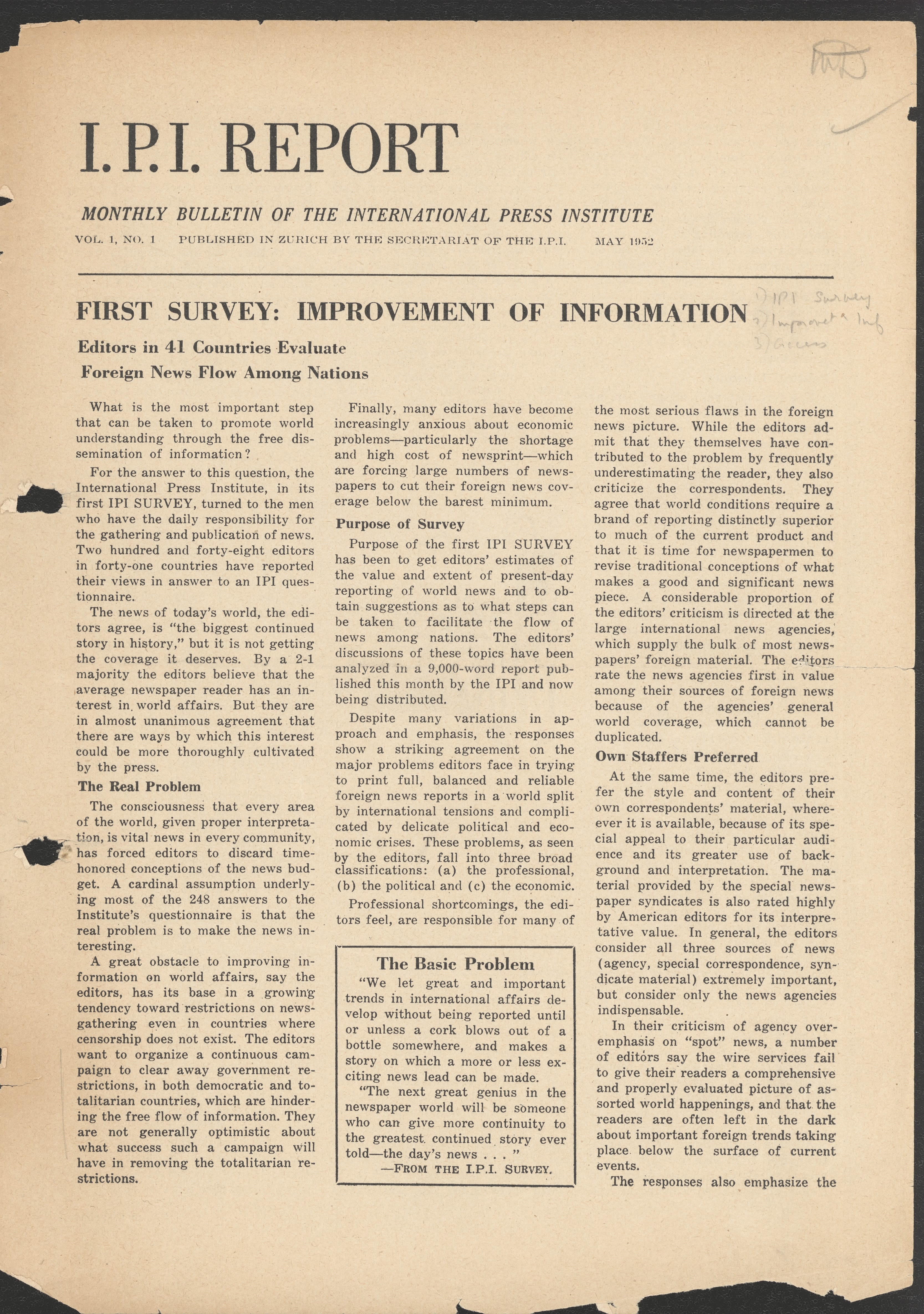

The first issue of the IPI Report announces the results of IPI’s global survey, May 1952

The first issue of the IPI Report announces the results of IPI’s global survey, May 1952

Founding a global network

In October 1950, at a time of fragile peace and rebuilding after World War II, 34 leading newspaper editors from 15 countries came together to found the International Press Institute. Determined to ensure that a free press would play a vital role in shaping a safer and more peaceful world, they responded to years of war and the manipulation of the press by creating a pioneering global network of professionals wholly independent of governmental, commercial, and political influence. Its mission:

"to advance the cause of a critical and independent journalism wherever it is practised; to correct the distortions of years of entrenched propaganda; and to dispel the fogs that clouded the relations between countries. "

Founding principles of IPI:

- The furtherance and safeguarding of freedom of the press: free access to the news, free transmission of news, free publication of newspapers, free expression of views;

- The achievement of understanding among journalists and so among peoples;

- The promotion of the free flow of accurate and balanced news among nations;

- The improvement of the practices of journalism.

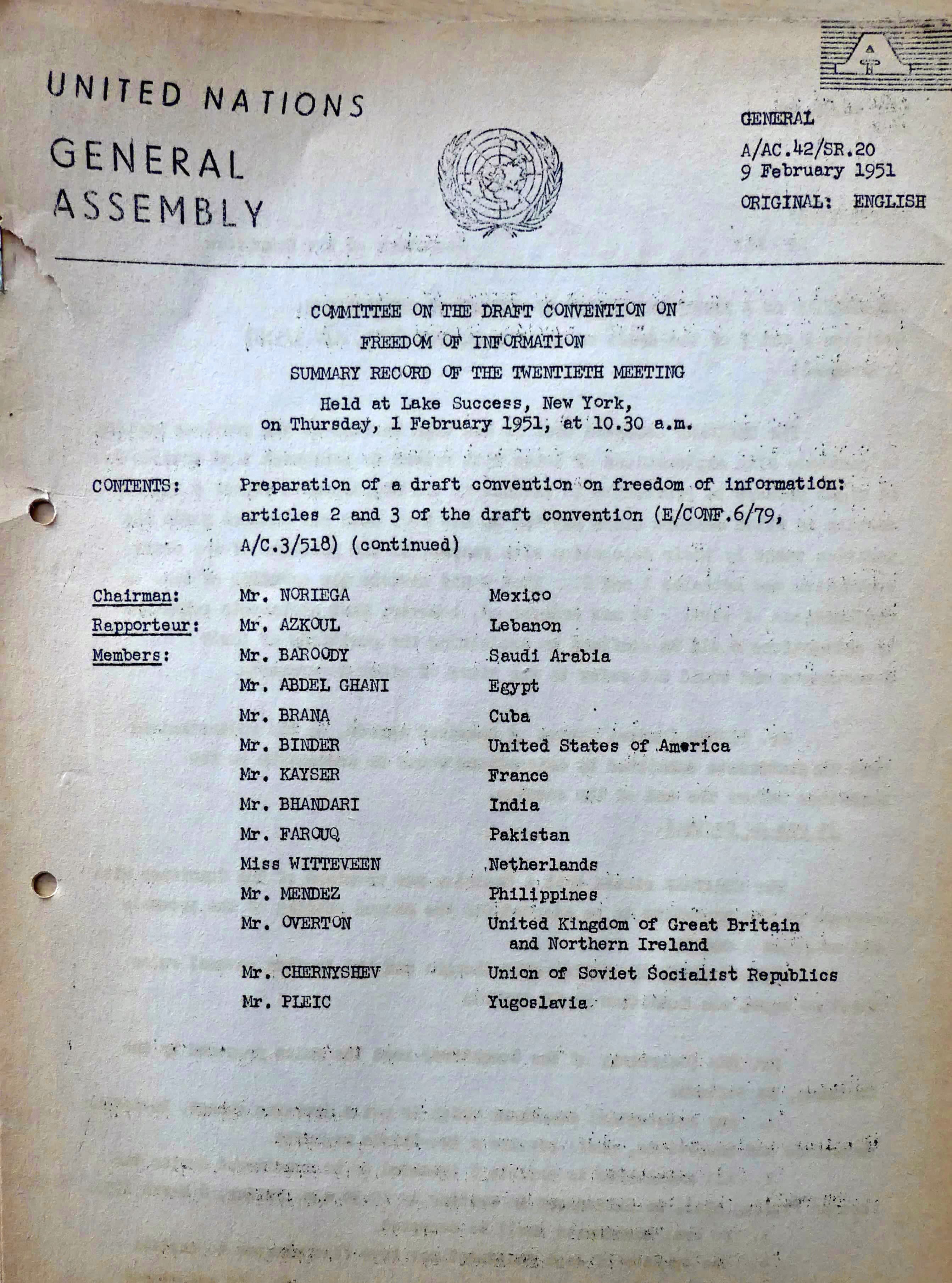

Record of the United Nations General Assembly Committee on the Draft Convention on Freedom of Information meeting in New York, February 1951

Record of the United Nations General Assembly Committee on the Draft Convention on Freedom of Information meeting in New York, February 1951

IPI Report cartoon depiction of the UN headquarters in New York, May 1952

IPI Report cartoon depiction of the UN headquarters in New York, May 1952

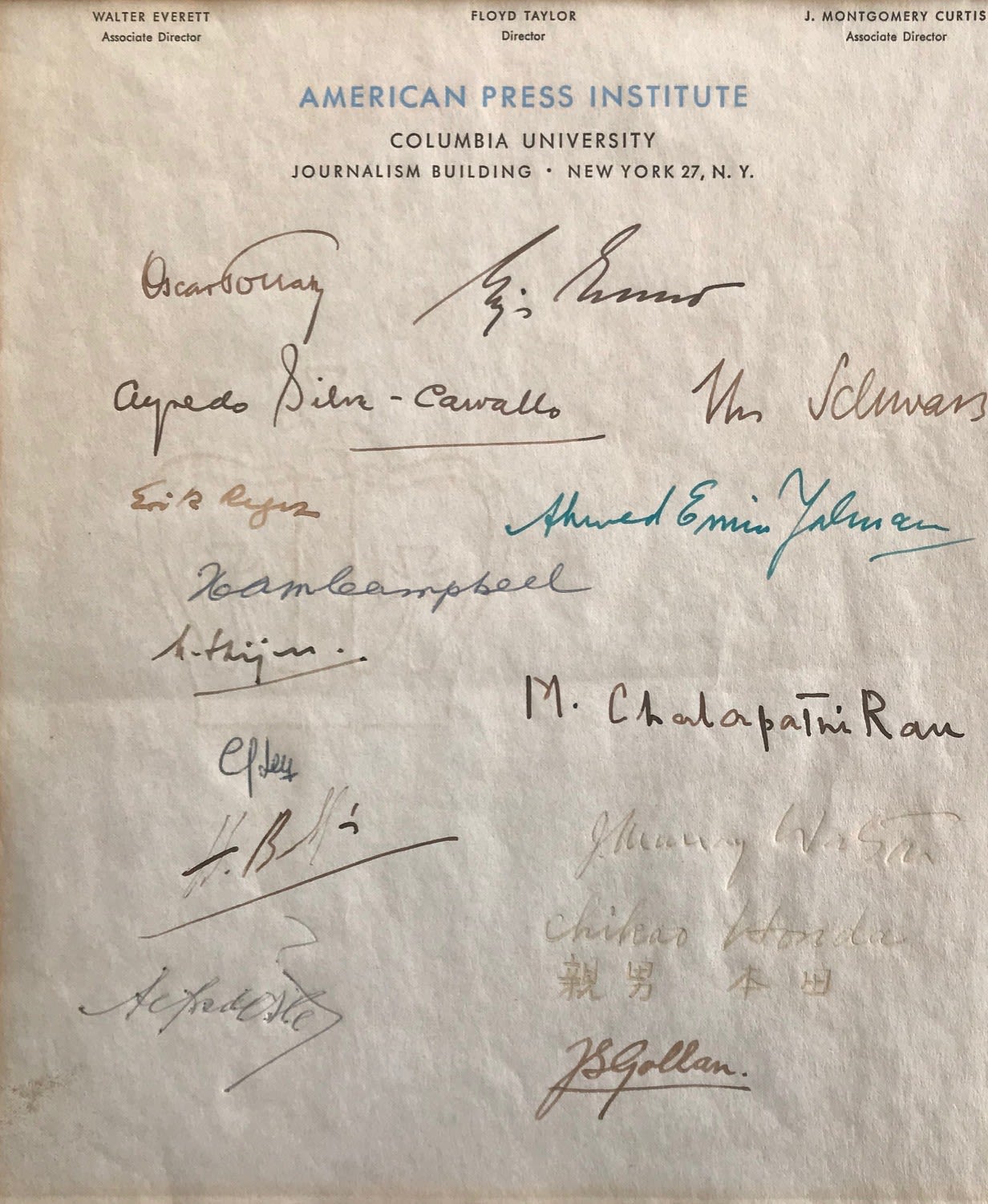

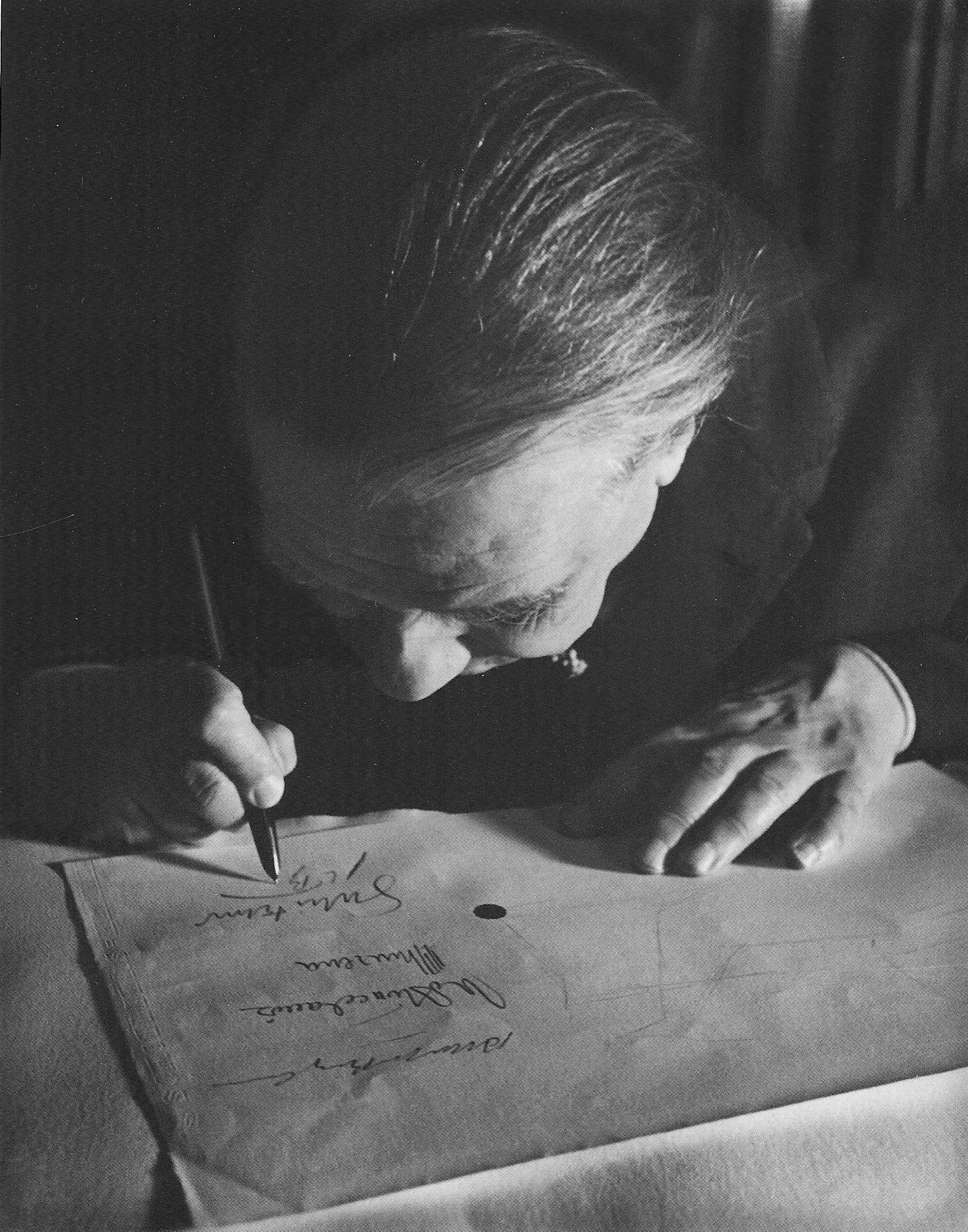

Signatures of IPI's founding editors (1950)

Signatures of IPI's founding editors (1950)

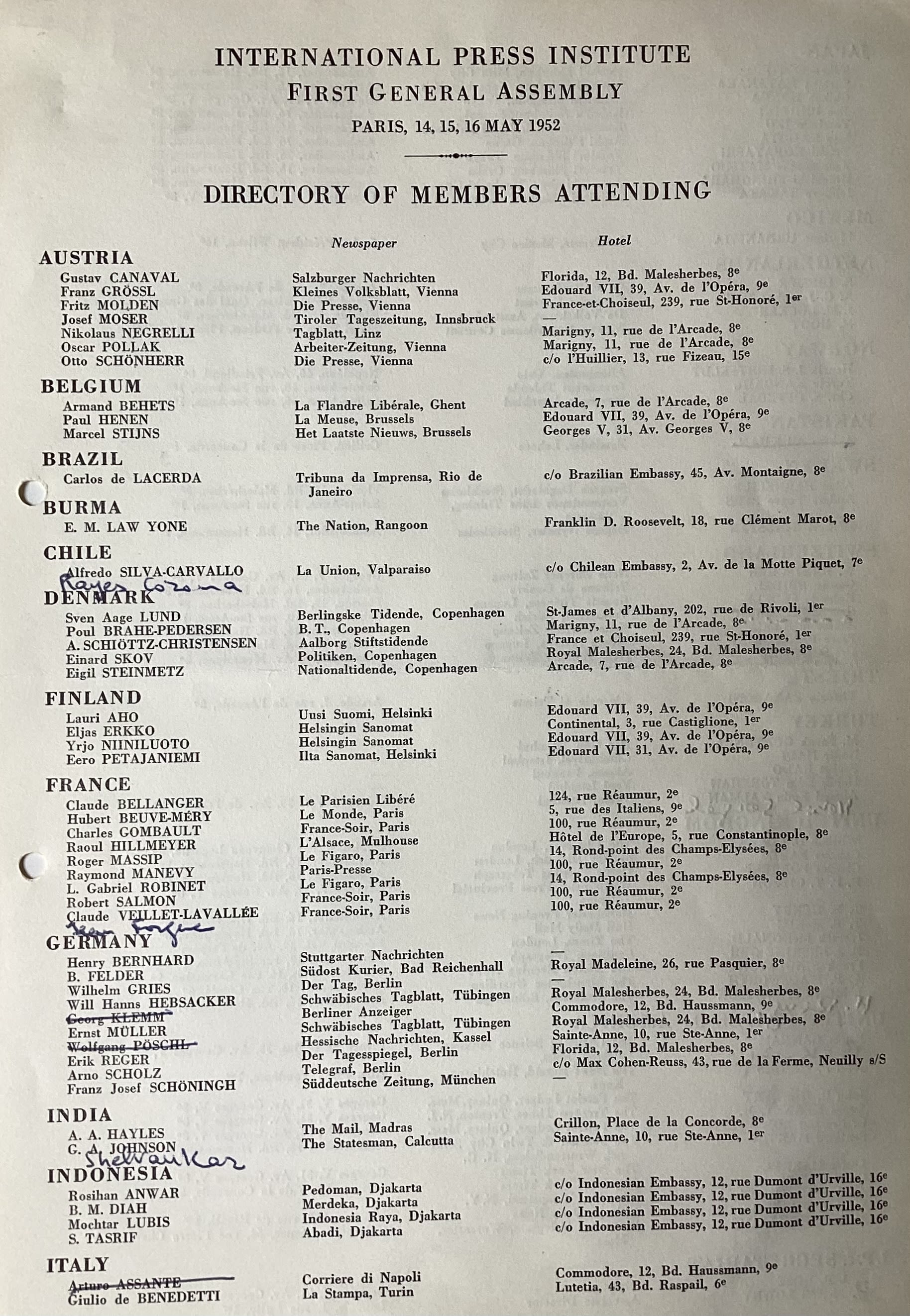

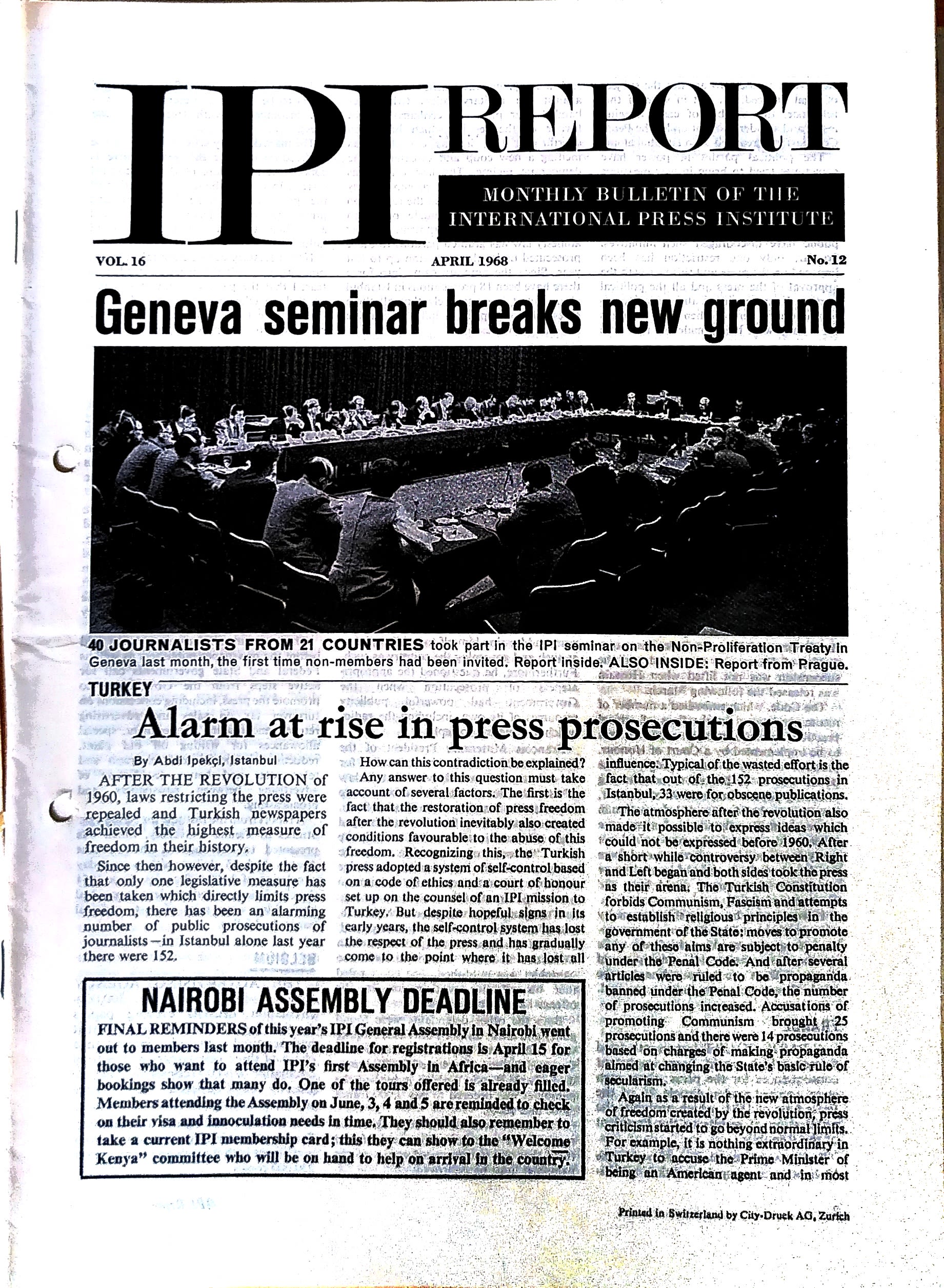

Directory of Members attending IPI’s first General Assembly in Paris, May 1952

Directory of Members attending IPI’s first General Assembly in Paris, May 1952

Directory of Members attending IPI’s first General Assembly in Paris, May 1952

Directory of Members attending IPI’s first General Assembly in Paris, May 1952

Building the foundations of dialogue

IPI's Secretariat was based in Zurich from 1952 to 1976, after which it moved to London (and later Vienna).

The first IPI General Assembly, held in Paris in 1952, brought together 101 editors from 21 countries to shape the plans of the new network, including how to improve the flow of the news — the amount and quality of information circulated by the press.

Having seen how ignorance and hatred of one’s neighbours had contributed to the carnage of World War II, IPI members sought to promote and strengthen local, regional, and continental reporting to prevent future strife.

At the same time, IPI national committees were hard at work coordinating meetings between newspaper editors and, before long, leaders of countries that had fought each other less than a decade earlier.

IPI members organized the first post-war meetings between journalists in France and Germany - who in turn set up the first post-war meeting between French and German leaders de Gaule and Adenauer - Turkey and Greece, and Japan, its Pacific neighbours, and the United States.

IPI Report front page on the first meeting between Greek and Turkish editors, April 1961

IPI Report front page on the first meeting between Greek and Turkish editors, April 1961

French President Charles de Gaulle (left) shaking hands with German chancellor Konrad Adenauer (right). Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv

French President Charles de Gaulle (left) shaking hands with German chancellor Konrad Adenauer (right). Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv

Staying ahead of the curve

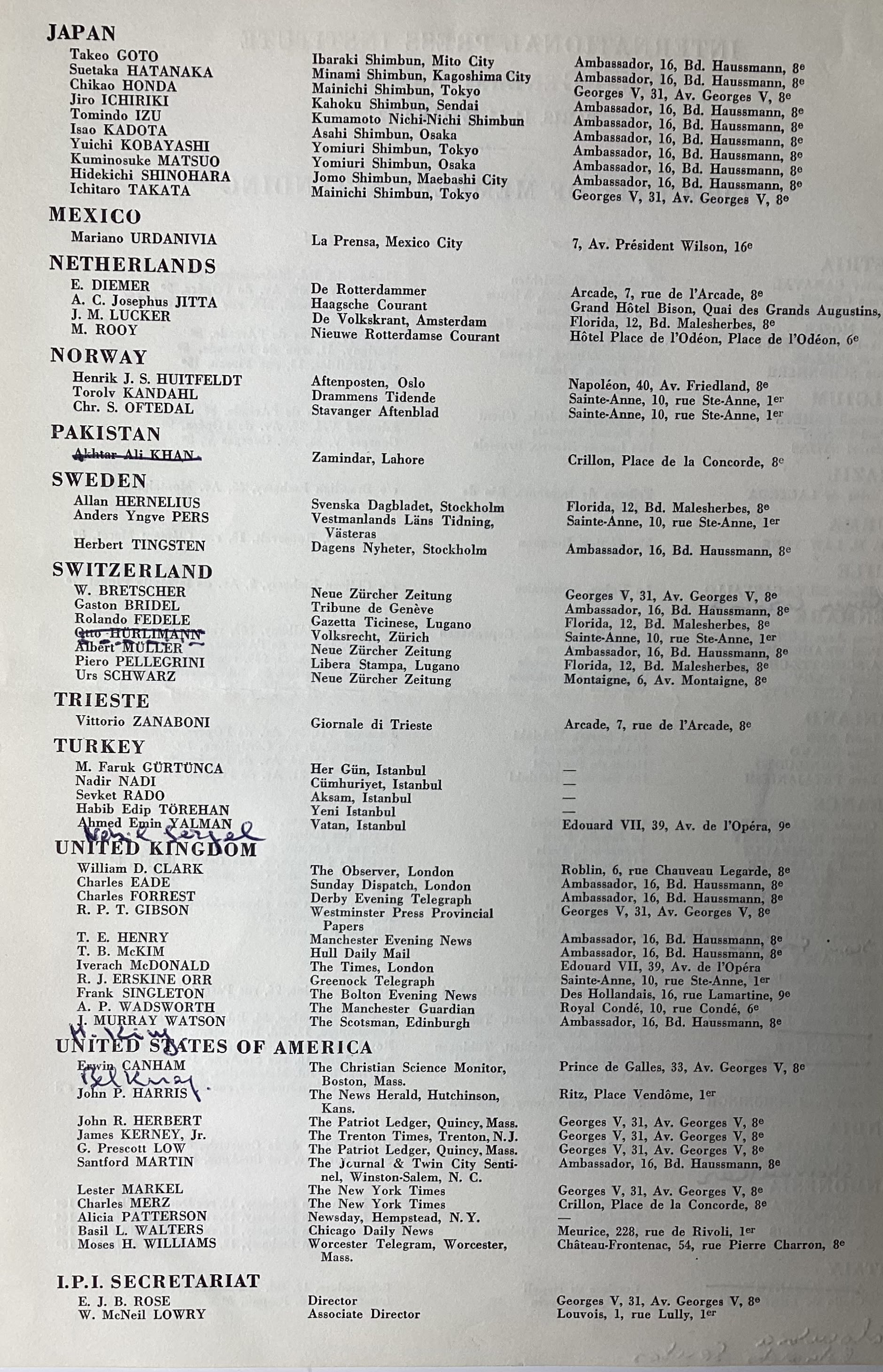

An integral part of the post-war rejuvenation of journalism was bridging gaps in knowledge and information, making specialist expertise accessible to a general audience. Science reporting in the atomic age, for example, helped explain both the arms race and the civilian uses of nuclear energy to anxious readers at a time when new scientific paradigms were reshaping human understanding.

Almost everything that is now known was not in any book when you went to school; you couldn't know it unless you had picked it up since. And this in itself presents a problem of communication that is nightmarishly formidable.

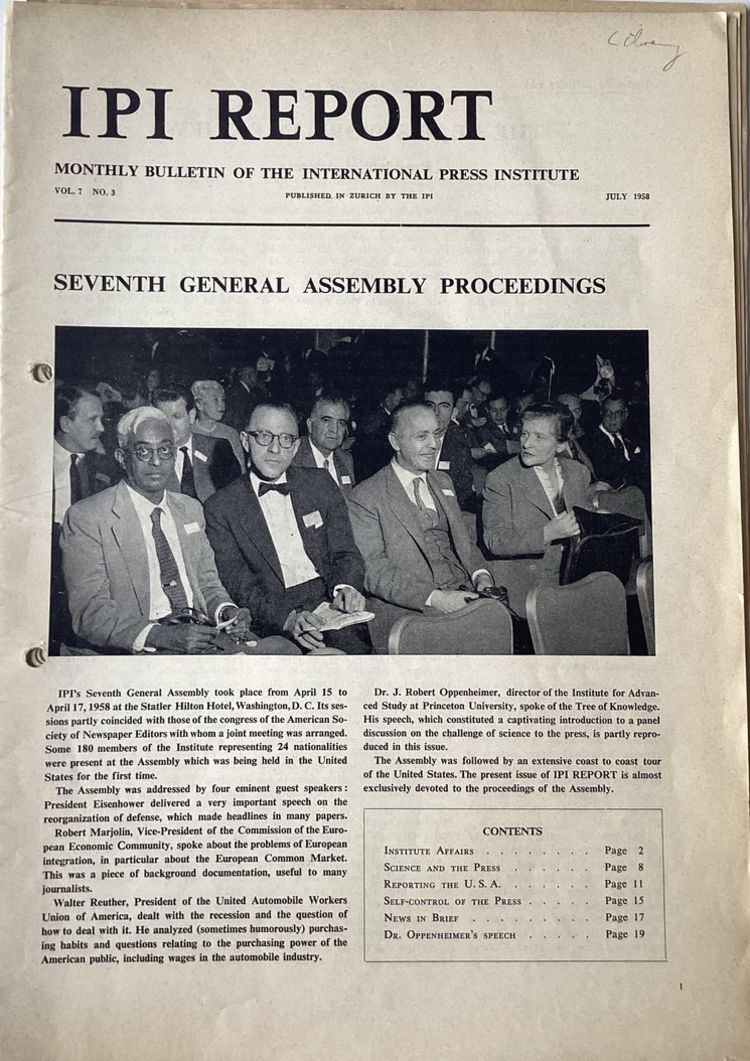

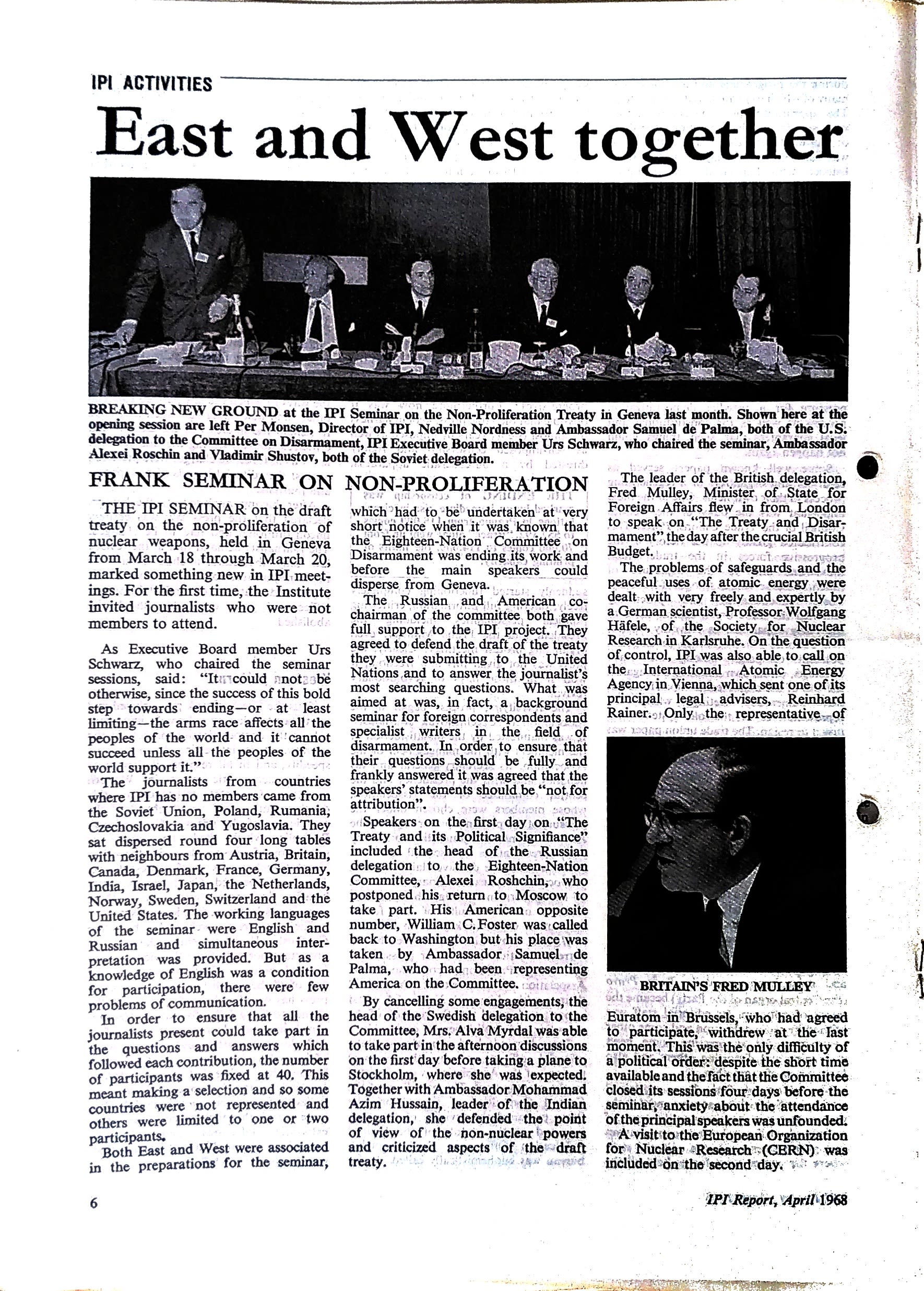

Nuclear reporting also provided a reason to bring together journalists from both Cold War blocs. In March 1968, IPI organized a ground-breaking seminar in Geneva on the Non-Proliferation Treaty, inviting — for the first time — non-member journalists from the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc states.

IPI Report on the challenges of reporting outer space, February 1959

IPI Report on the challenges of reporting outer space, February 1959

IPI Report front page on the 7th General Assembly, Washington DC, July 1958

IPI Report front page on the 7th General Assembly, Washington DC, July 1958

J. Robert Oppenheimer, 'The Tree of Knowledge,' IPI Report, July 1958

J. Robert Oppenheimer, 'The Tree of Knowledge,' IPI Report, July 1958

IPI Report front page coverage of the non-proliferation seminar in Geneva, April 1968

IPI Report front page coverage of the non-proliferation seminar in Geneva, April 1968

Nuclear reporting also provided a reason to bring together journalists from both Cold War blocs. In March 1968, IPI organized a ground-breaking seminar in Geneva on the Non-Proliferation Treaty, inviting — for the first time — non-member journalists from the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc states.

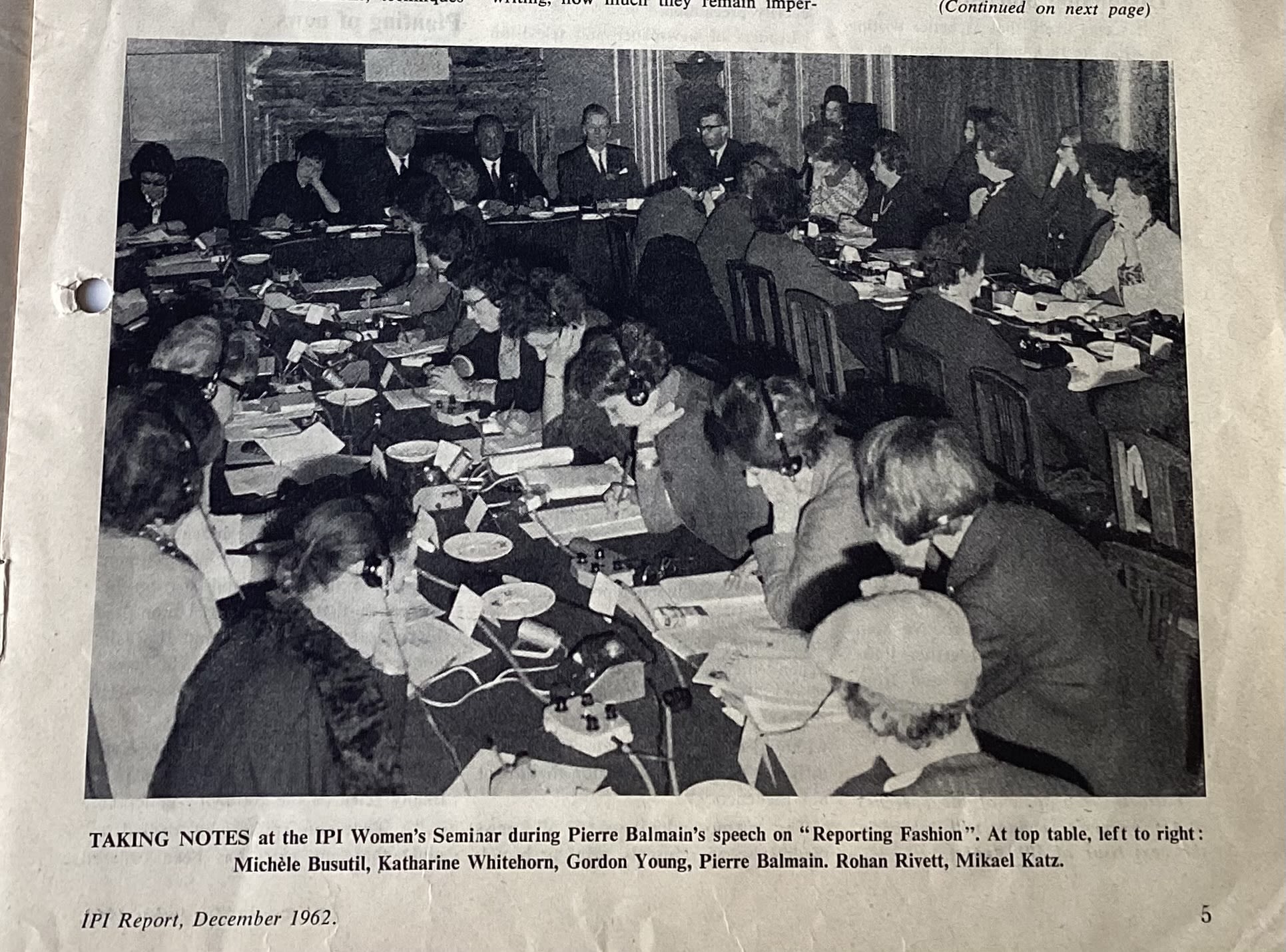

Staying ahead of the curve also meant expanding both the readership and the very scope of the journalism profession. In 1962, IPI brought together journalists, editors, medical professionals, and even a fashion designer to discuss how the print media could attract more women readers — a conversation that, at the time, often centred on “the woman’s page”. In her summary for IPI Report, Katharine Whitehorn of The Observer noted:

When women were breaking into journalism most of the clever ones concentrated on writing men’s prose on men’s topics and avoided the woman’s page like death… But now these stalwarts have crashed down the barriers, it is time for the distinction to go.

IPI report on the non-proliferation seminar held in Geneva, November 1961

IPI report on the non-proliferation seminar held in Geneva, November 1961

Katharine Whitehorn, 'Paging All Women', IPI Report, December 1962

Katharine Whitehorn, 'Paging All Women', IPI Report, December 1962

Katharine Whitehorn, 'Paging All Women,' IPI Report, December 1962

Katharine Whitehorn, 'Paging All Women,' IPI Report, December 1962

Letter from Mohamad Sarfaz, Editor of The Pakistan Times, to Rohan Rivett of IPI, November 1961

Letter from Mohamad Sarfaz, Editor of The Pakistan Times, to Rohan Rivett of IPI, November 1961

Advice: better mofussil news! Mofussil is a word borrowed from Bengali, Farsi and Arabic and in India it referred to places outside the three cities of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, in other words, rural and regional areas. The Active Newsroom, 1962.

Advice: better mofussil news! Mofussil is a word borrowed from Bengali, Farsi and Arabic and in India it referred to places outside the three cities of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, in other words, rural and regional areas. The Active Newsroom, 1962.

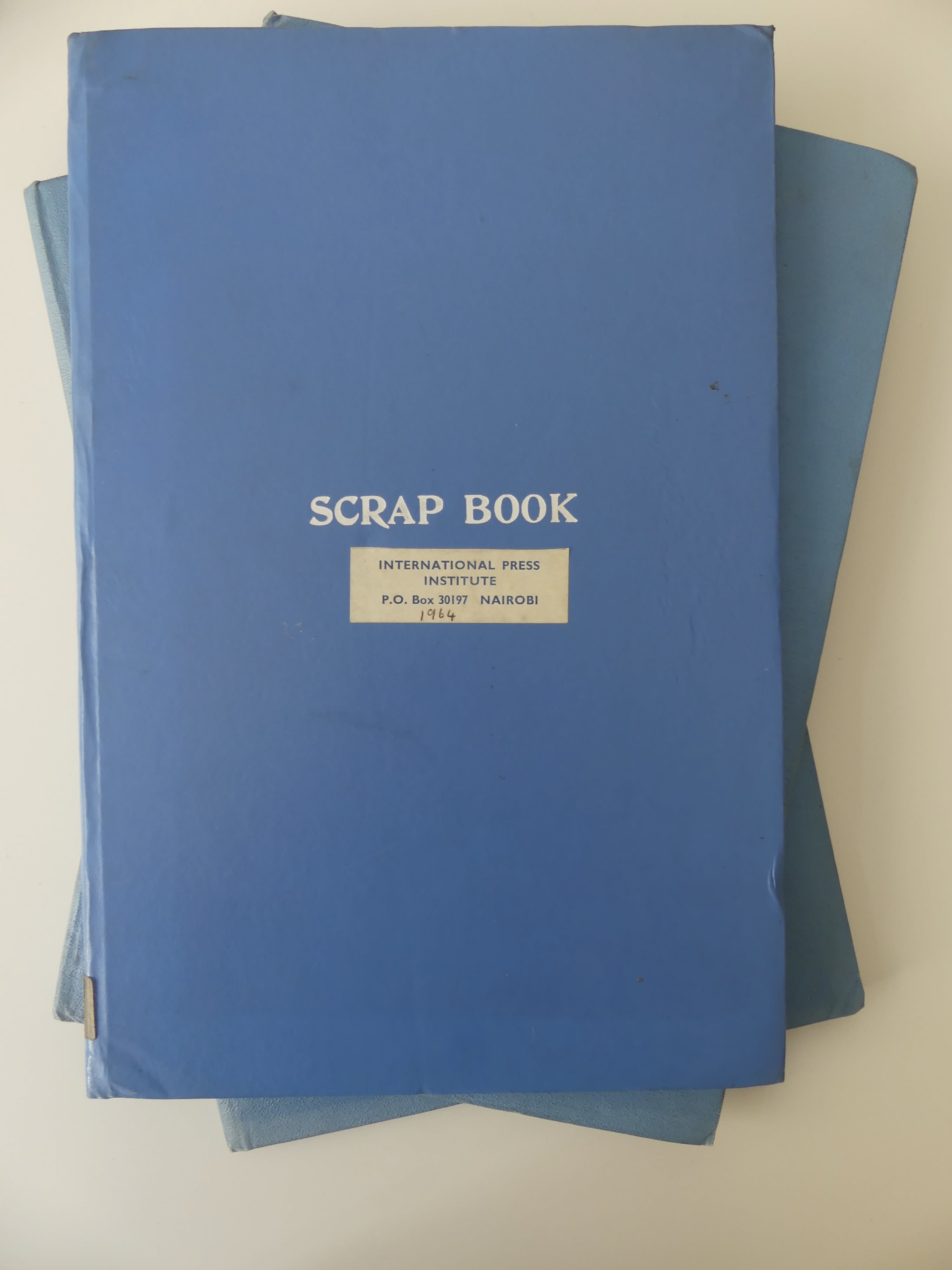

IPI Nairobi scrapbooks

IPI Nairobi scrapbooks

Articles in the Nairobi scrapbook

Articles in the Nairobi scrapbook

Knowledge + skills = power

A country's decolonization and the proclamation of national independence do not necessarily mean that there are more countries with a free press.

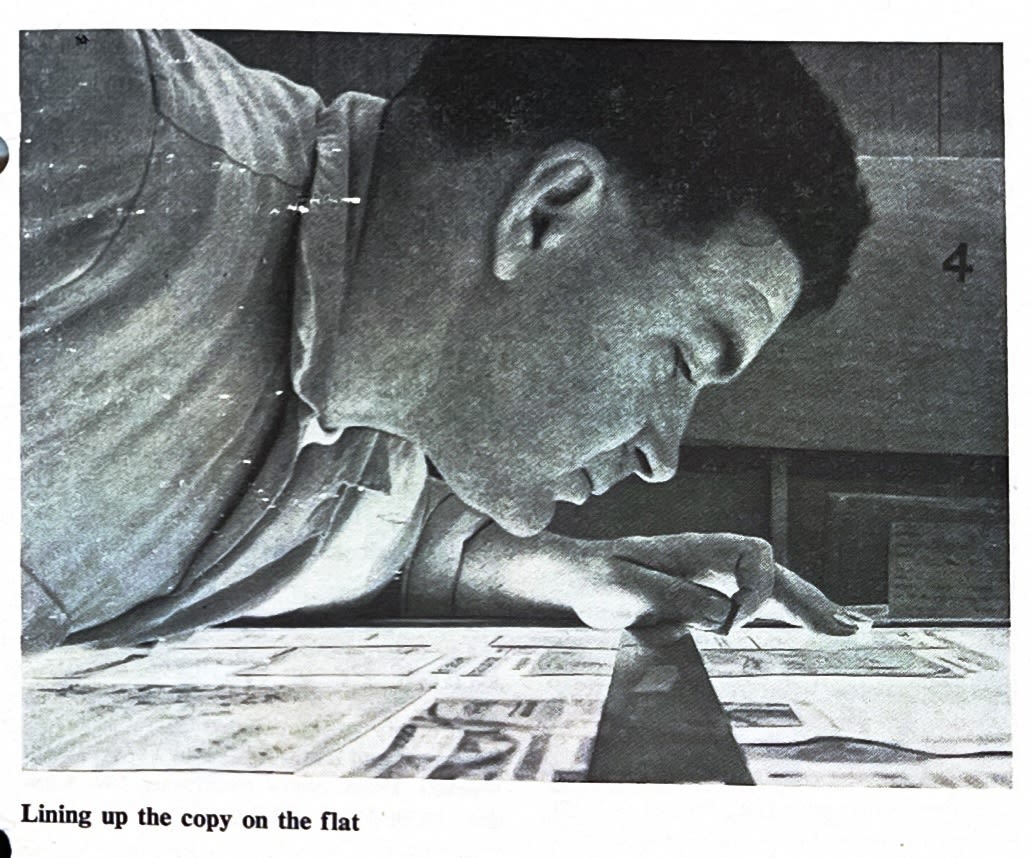

In newly independent post-colonial states, IPI organized regional seminars to share knowledge and build skills such as photojournalism, layout, and critical interviewing techniques. The goal was to make quality reporting accessible to the widest possible readership, despite challenges including uneven literacy rates and the high cost of newspapers.

For example, surveys of local journalists and regional conferences revealed that Asian newspapers’ links with former colonial rulers often dominated and distorted news coverage. The solution: to open channels of exchange and dialogue with colleagues in neighbouring countries.

IPI hosted the first meeting of Anglophone and Francophone journalists in Africa, who went on to establish their own training schemes at the universities of Nairobi and Lagos (later the Nigerian Institute of Journalism).

Local expertise proved crucial to this effort. Anti-apartheid networks inside South Africa, along with émigré journalists, helped shape IPI’s Africa programme, which was tailored to the differing post-colonial Anglophone and Francophone contexts.

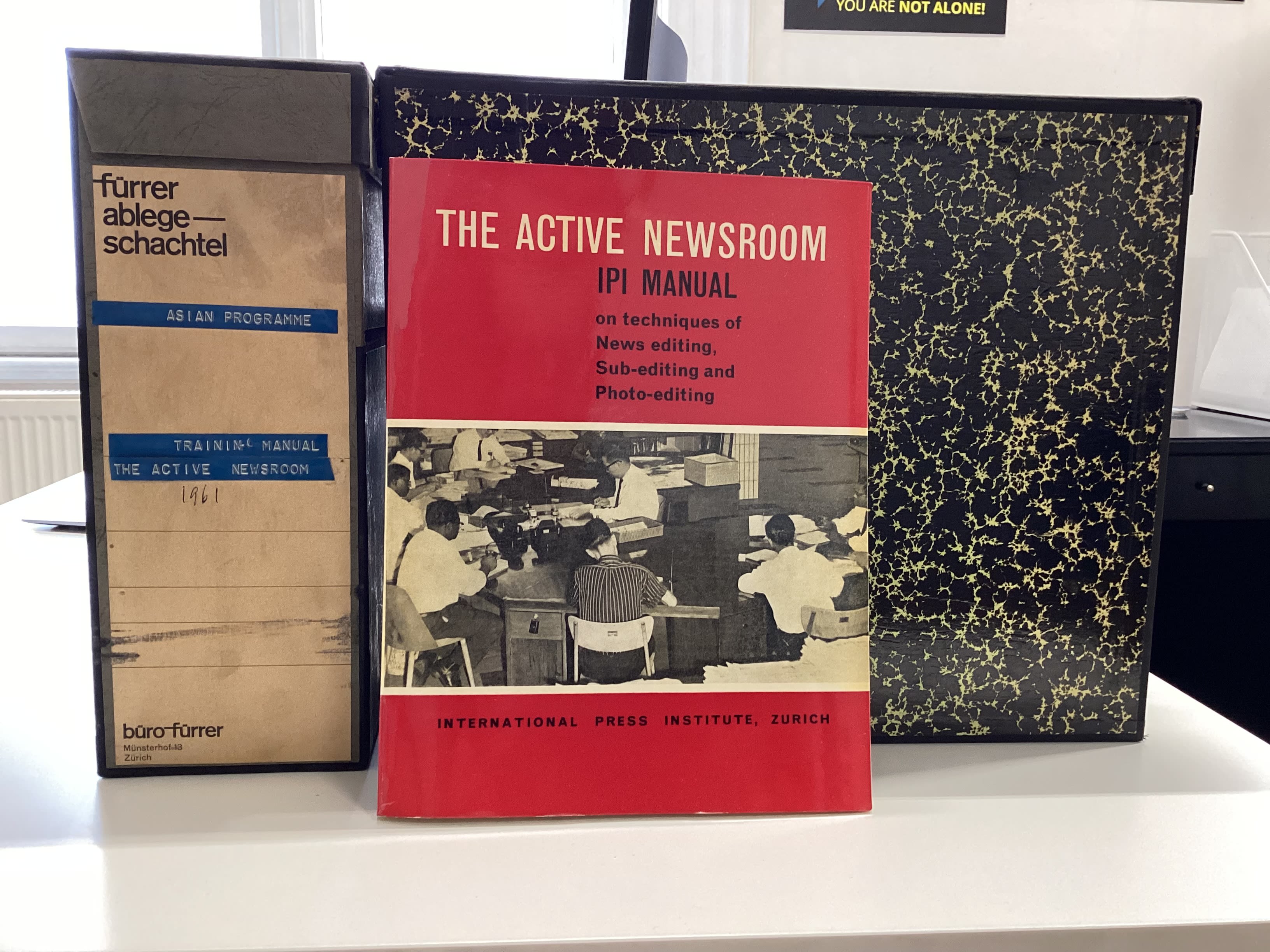

Key publications: The Active Newsroom (1962) and The African Newsroom (1972).

The Active Newsroom, 1962

The Active Newsroom, 1962

The African Newsroom, 1972

The African Newsroom, 1972

When the walls come tumbling down...

Nothing lasts forever, not even dictatorships. Developing critical media in newly liberated societies required solidarity and support for local journalists and leaders in their struggle for a free press.

From the start, IPI supported members in emerging democracies, organizing training seminars on political reporting for German journalists in the 1950s, who later passed on their knowledge to Spanish colleagues after the death of dictator Francisco Franco. In 1987, the IPI General Assembly took place in Buenos Aires and Montevideo, helping to build free media networks after the end of military rule in Argentina and Uruguay.

In 1990, a forum for newly independent Central and Eastern European media outlets offered guidance on improving printing and distribution, as well as management and training models. IPI moved from London to Vienna in 1992 to support the post-communist media transition. Best practices for post-apartheid journalism in South Africa also shaped the agenda at IPI’s General Assembly in Cape Town in 1994 — and again in 2014.

IPI Report on the first General Assembly in Latin America, held in 1987 to mark the fall of military dictatorships in Argentina and Uruguay.

IPI Report on the first General Assembly in Latin America, held in 1987 to mark the fall of military dictatorships in Argentina and Uruguay.

Protesters sitting on the Berlin Wall, November 1989. Fortepan / Péter Horváth

Protesters sitting on the Berlin Wall, November 1989. Fortepan / Péter Horváth

Nelson Mandela addresses the IPI Congress in Cape Town, 1994

Nelson Mandela addresses the IPI Congress in Cape Town, 1994

• CENSORSHIP

From information shortages to flooding the zone

In the years following World War II, journalism was marked by shortages — of newsprint, of training opportunities for journalists, and of reliable information itself. Today, the opposite problem exists: an overwhelming excess of sources, channels, and competing versions of reality that can similarly serve to deny, obstruct, and undermine access to trustworthy reporting.

Yet journalists have always found innovative ways to work around restrictions on the flow of information, as well as political, economic, and legal threats to their work. IPI research director Armand Gaspard observed at the General Assembly in 1962:

Everywhere in the world where freedom of the press is not a lost cause, it would seem that solidarity among journalists is the best safeguard.

IPI Report cartoon of two figures writing on the ground threatened by a figure holding a weapon, 1958

IPI Report cartoon of two figures writing on the ground threatened by a figure holding a weapon, 1958

Censorship, IPI Report 1952

Censorship, IPI Report 1952

Self-defence through solidarity

Some stories are so big that they cannot be covered just by one newspaper, one service, or one voice. In 1953, Palmer Hoyt, editor and publisher of The Denver Post, argued:

The tonnes of white space, the magic of electronics and the wonders of hot type are in themselves lifeless tools in the hands of a demagogue unless newspapermen can freshen up their ethical sense; pool their brains; integrate their efforts; revise their concepts of publication and determine that the ‘big lie’ shall not go unchallenged.

IPI Report article on how to report on McCarthy(ism), August 1953

IPI Report article on how to report on McCarthy(ism), August 1953

When channels were shut in one place, journalists continued the story elsewhere or found a workaround. During the Katanga-UN conflict in the early 1960s — a series of clashes between UN peacekeepers and the secessionist gendarmerie of Katanga after the province broke away from the newly independent Congo — correspondents faced attacks on transmitters and a lack of reliable information. They overcame these obstacles by working together.

Solidarity…The agency men organized a pool for transmitting their messages alternately; the photographers worked as a team, and every journalist taking his turn to make the journey to Rhodesia carried with him dozens of articles, cables or films for his colleagues and saw that they were eventually dispatched by cable, post or aeroplane.

Later, during the 1972 Indo-Pakistani war, both sides performed “write-in censorship” on all news material leaving the country. Entire newspaper stories were cut, while international TV crews faced even harsher interference. Their solution was to use Eastman film, which neither India nor Pakistan could process at the time — forcing the film to be transported out of the country unedited.

Reading between the lines

Whether in totalitarian or democratic societies, journalists must decode official statements, interpret silences, and piece together what is left unsaid. Even without formal censorship, truth often emerges only by seeking out parallel and unofficial sources.

At a 1963 General Assembly panel on the Soviet Union, Le Monde Moscow correspondent Michel Tatu confirmed that after Stalin, pre-censorship was no longer a problem for foreign correspondents. Instead, journalists had to learn how to interpret “the form of certain silences, anomalies, small facts which seem out of proportion to the events they conceal”.

That same year in Stockholm, the term “misinformation” was used for the first time at an IPI General Assembly panel: ‘National Security: Information and misinformation by governments.’ It referred to the US government’s “management” of the news during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The White House had sought voluntary assistance from the press at the same time as the Pentagon planted misleading stories. During a debate on balancing national security interests and the duty to report, Clark R. Mollenhoff of The Des Moines Register argued:

If the press of this nation is interested in remaining free, it will be necessary to pay more attention to principle and less attention to expediency or personalities… If you have lost your capacity for balanced independent thinking, then you are a likely candidate for the title of ‘high-level handout collector’.

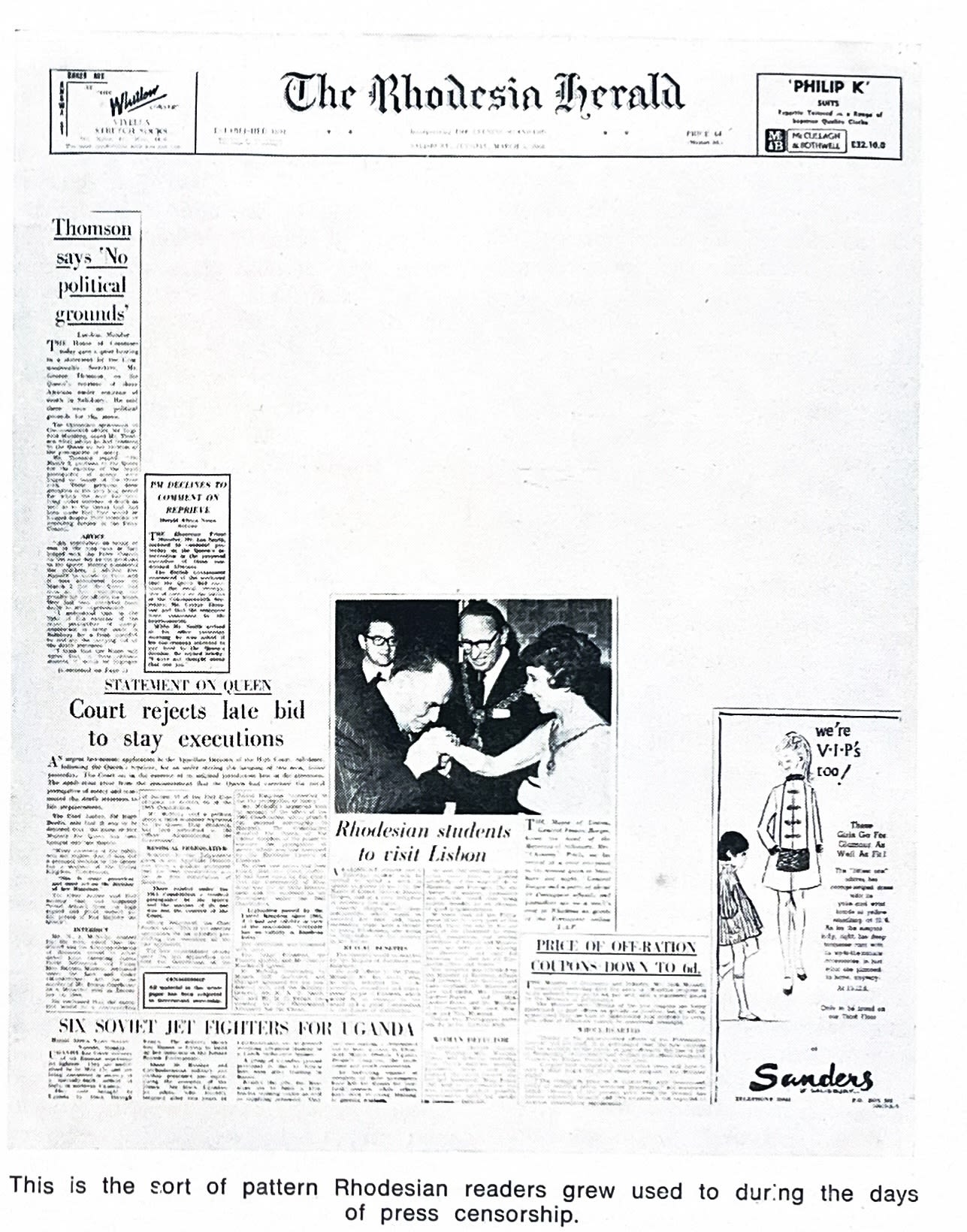

IPI Report on press reading practices in the Soviet Union, October 1980

IPI Report on press reading practices in the Soviet Union, October 1980

Fill in the blanks, break taboos...

Silence and secrecy have always posed problems for journalists. After being expelled from Ghana for her critical reporting, Sunday Times correspondent M.S. Dorkenoo exposed how news articles were suppressed and framed the dilemma starkly: Accept compromise or face silence.

This is a matter which every newspaper, every editor, every journalist must decide for himself. And it is all to the good if not everyone makes his stand at the same place.

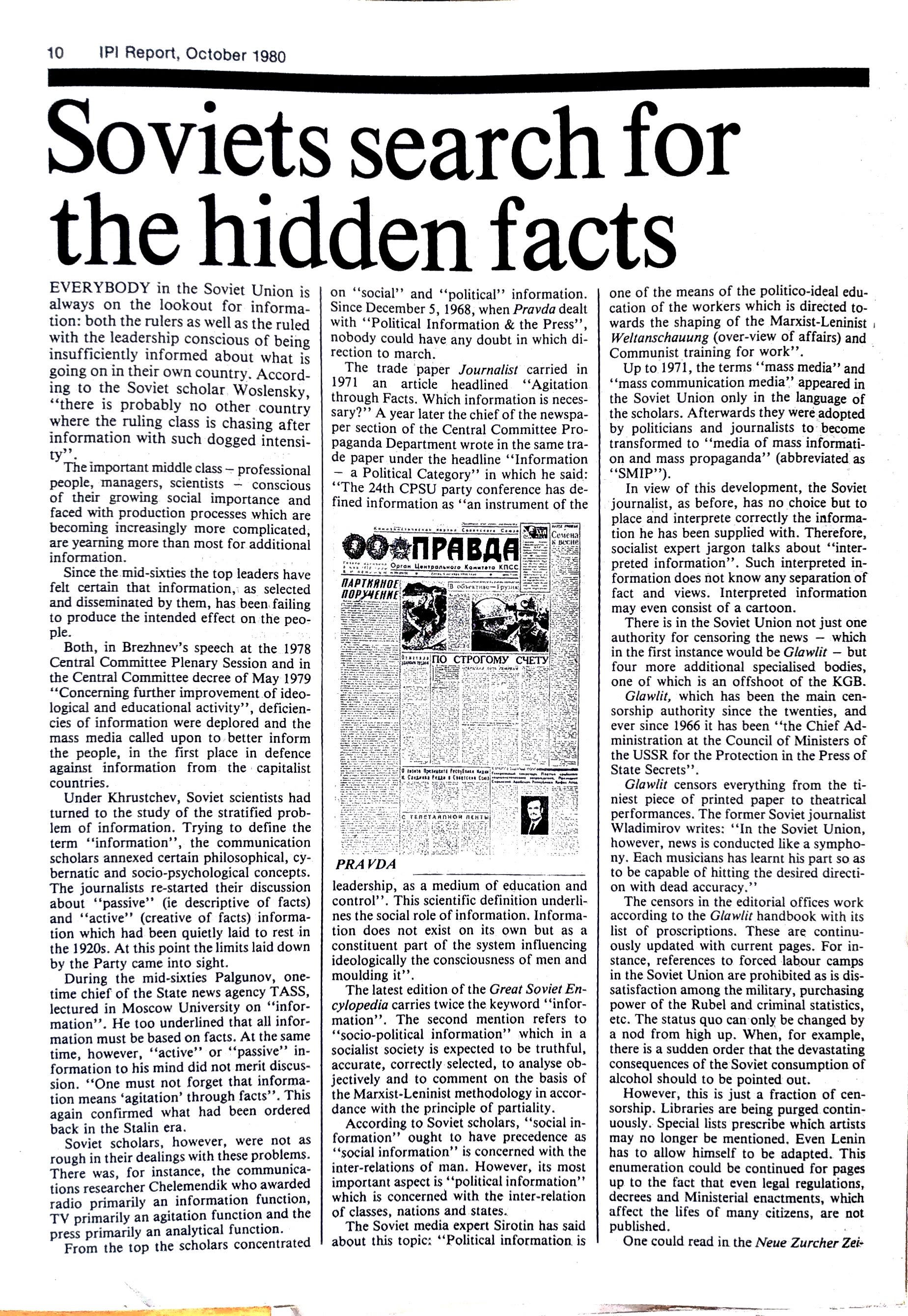

After Ian Smith’s government in Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) forbade the use of blank spaces to indicate where censorship cuts had been made, IPI published the censored, half-empty front page of The Rhodesia Herald in 1966 and issued a statement condemning the government’s “steps to turn the press of Rhodesia into a mere mouthpiece of the authorities”.

As the Prague Spring unfolded, IPI published articles by Czechoslovak journalists before, during, and after the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968. From Prague, Jan Vašek observed that breaking taboos had unleashed an unstoppable force:

First rumours, then speeches by some progressive leaders of the party, then the paralysis which overwhelmed the censors under the pressure of public opinion, and then abolition of censorship at the end of February, brought the story in full to the people.

White space on the front page of the redacted 1966 Rhodesia Herald

White space on the front page of the redacted 1966 Rhodesia Herald

Postcard to IPI staff from Czech journalist Emil Sik, 1969

Postcard to IPI staff from Czech journalist Emil Sik, 1969

Postcard to IPI staff from Czech journalist Emil Sik, 1969

Postcard to IPI staff from Czech journalist Emil Sik, 1969

Self-censorship

How should journalists respond to repression — by self-censoring or by resisting? The debate stretches back decades. In 1967, Greek newspaper proprietor Eleni Vlachou (Helene Vlachos) gave a dramatic answer: Rather than compromise, she shut down her paper Kathimerini in protest at the military coup and was placed under house arrest.

Eleni Vlachou (Helen Vlachos) open letter, IPI Report, October 1967

Eleni Vlachou (Helen Vlachos) open letter, IPI Report, October 1967

Don’t believe for a moment that what the Foreign press writes leaves the colonels cool and undisturbed, that they don’t care. They care desperately. They publish with delight the smallest crumb of flattery… By now people with sense the world over know what has happened to Greece. And I ask them to worry about it. It may prove contagious.

Following the Iranian revolution of 1979, IPI published a booklet by Amir Taheri about the fate of the “noose pepper” — the earliest Farsi word for newspaper. To survive, publications had to reinvent themselves entirely, smuggle out stories, or go into exile. The earliest newspapers had overcome the lack of a modern political vocabulary by producing papers “entirely in verse, or a mixture of verse and rhymed prose”, or adapting the popular adventure-story genre to attract readers.

Alternatively, one might embrace censorship as a creative challenge. Robert Cox, a former editor of The Buenos Aires Herald, recalled:

Borges began to extol censorship on the grounds that it sharpened up your talents, honing your style so that it can cut like a razor. Censorship was good for writers, he said, even erotic ones. He quoted Swinburne with relish and said that his erotic power was the result of the discipline imposed by censorship. I went away unconvinced. Borges himself was probably only half-convinced, but he enjoyed being contrary and the idea of a triumph over censorship through pure style alone must have appealed to him.

Jorge Luis Borges writing, 1963. Wikimedia / Alicia D'Amico

Jorge Luis Borges writing, 1963. Wikimedia / Alicia D'Amico

• TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE

The IPI Report (1952-2005)

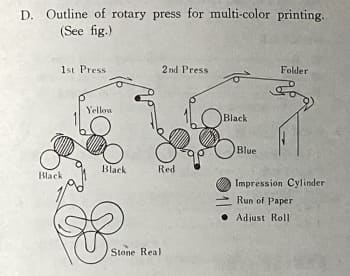

The IPI Report itself embodies the technical changes it chronicled. Hand-drawn cartoons gradually gave way to monochrome photographs, which were later joined by colour images and eventually advertisements.

Within the pages of IPI Report, debates about technological change unfolded across decades. Each new shift was seen either as progress or decline, threat or opportunity — reshaping not only how journalists reached readers but also the very practices of the newsroom and the audiences they served.

With every wave of change, journalists debated whether new technologies would destroy their profession or set it free. The lesson, repeated time and again, was clear: Adapt and use technology wisely — before it uses you.

PI Report cartoon of a typewriter and a sword, June 1952

PI Report cartoon of a typewriter and a sword, June 1952

IPI Report Cartoon of punched tape and hieroglyphics, June 1952

IPI Report Cartoon of punched tape and hieroglyphics, June 1952

IPI Report cartoon of a journalist using two telephones, smoking and making notes by hand, December 1952

IPI Report cartoon of a journalist using two telephones, smoking and making notes by hand, December 1952

Pullitzer Prize-winning photo by Yasushi Nagao of the 1960 assassination of Japanese politician Inejirō Asanuma, reproduced in The Active Newsroom, 1962

Enter the cameras

From the 1950s onward, journalists debated the moral authority of the written word in a world growing ever more visual and immediate. To compete with the flashy “cheesecake” of other media, both reporters and their subjects had to raise their game.

The 1952 U.S. presidential race and the 1954 televised Army-McCarthy hearings posed both a challenge and an opportunity for newspapers, testing their ability to compete with the speed and spectacle of television:

Editors and reporters must collaborate to produce faster, more accurate, more objective, and more complete news accounts than ever before if readers’ interest and confidence are to be maintained.

The next task was to help the news come alive with the help of trained photographers, combining intuition, psychological discernment, lightning reaction, and a highly developed sense of tact.

Editors must know exactly what they want… and train a team of photo reporters able to focus their lenses on the heart of the matter… The younger generation is extremely picture conscious and receptive to the ‘new look’ in photography.

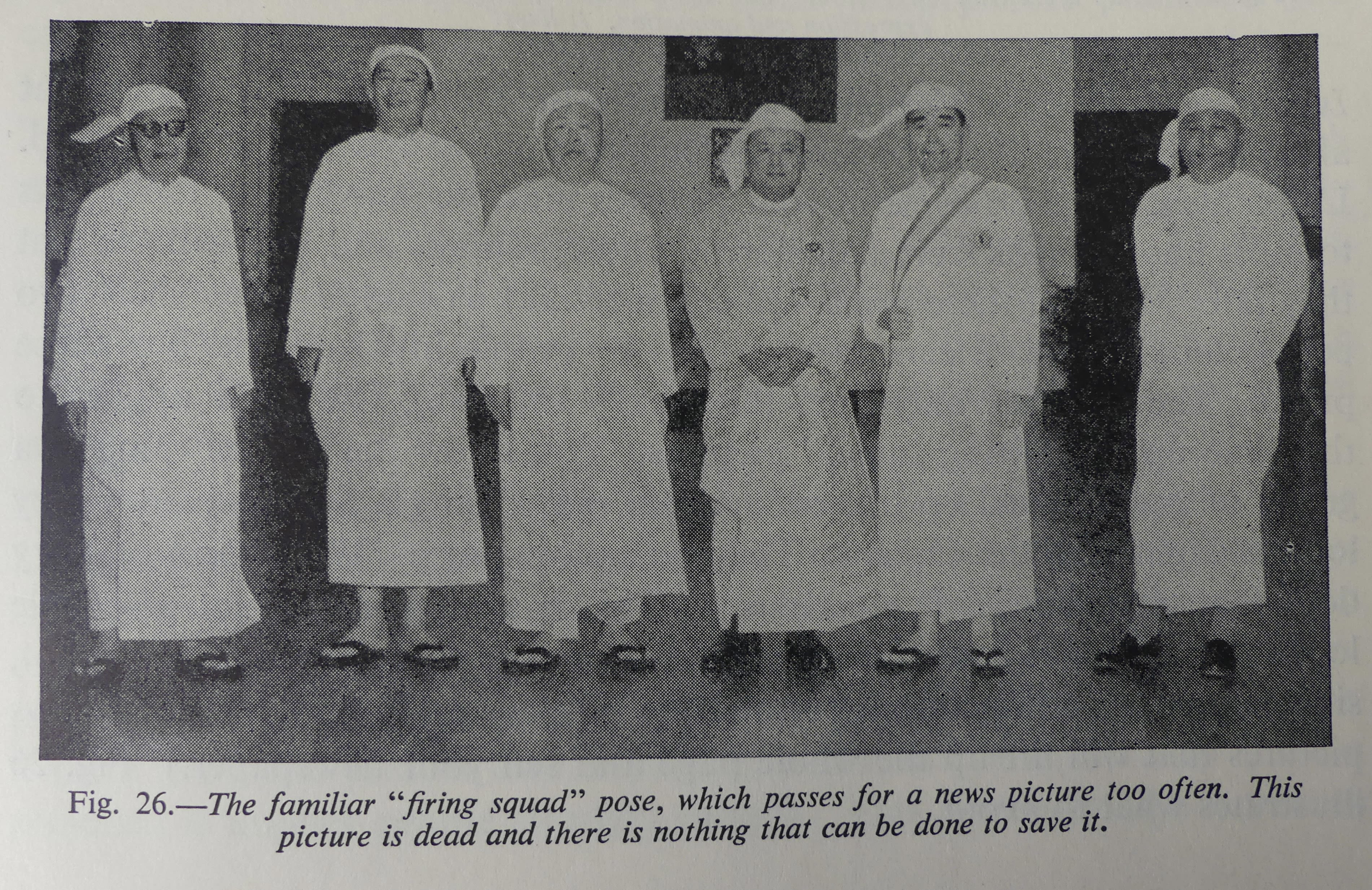

More advice from The Active Newsroom on how not to take group photos

More advice from The Active Newsroom on how not to take group photos

A press photographer at work in Hungary in the 1960s. Fortepan / Sándor Bojár

A press photographer at work in Hungary in the 1960s. Fortepan / Sándor Bojár

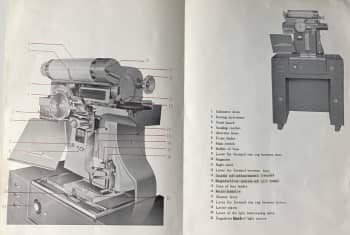

IPI Report on the latest image reproduction techniques, November 1959

IPI Report on the latest image reproduction techniques, November 1959

IPI Report on the new televised political debates, September 1952

IPI Report on the new televised political debates, September 1952

Adapting to change

Flexibility and the sharing of know-how have always been the sharpest tools of the trade. Reacting to the early rise of television, newspaper editors seized on new technologies to offer more charts and graphs, and more exclusive stories that TV could not provide. Above all, they invested in skilled technicians to bring readers what television still lacked — colour.

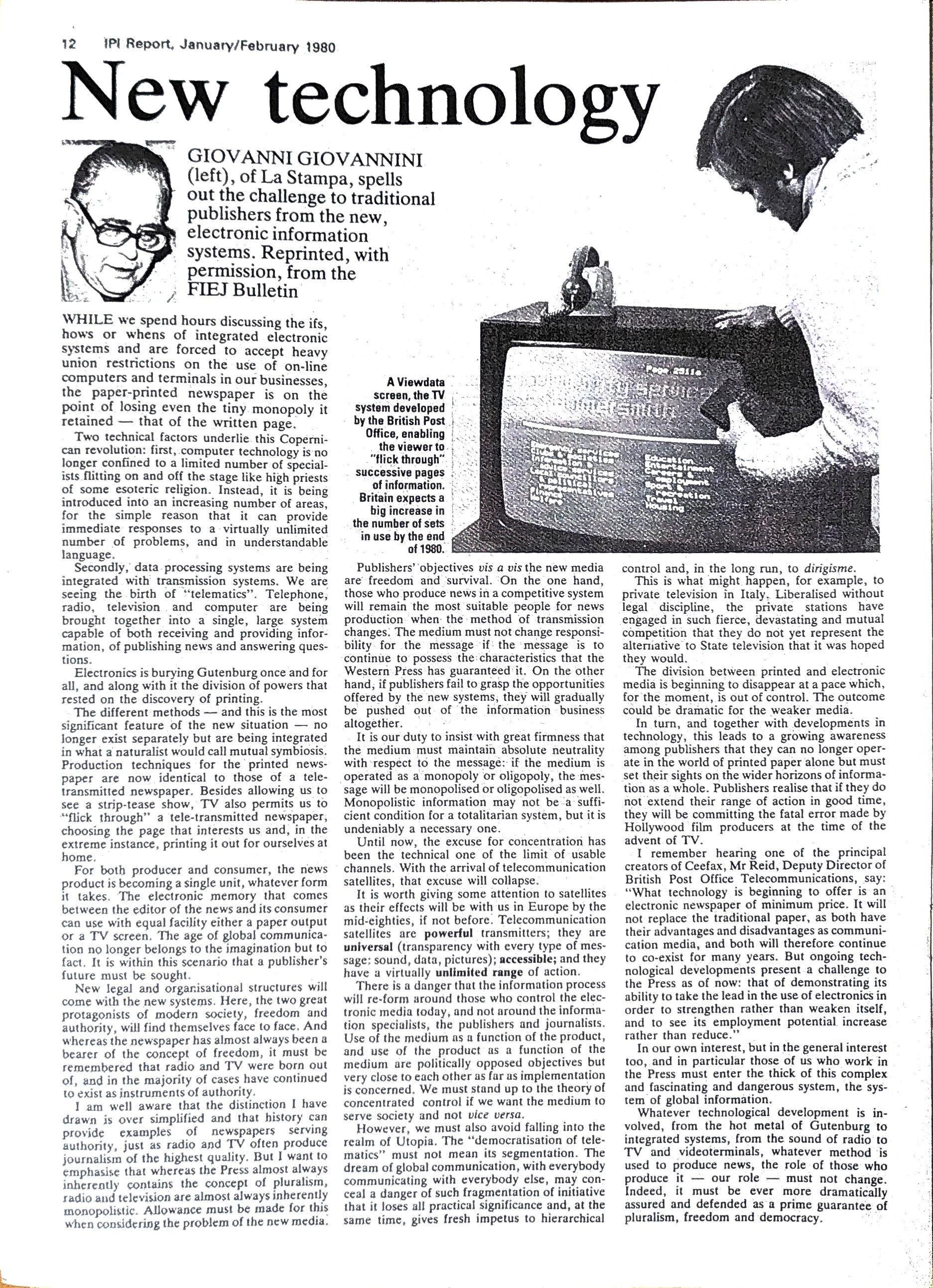

In the 1980s, as power struggles between private media owners began to stack up casualties, Giovanni Giovannini of La Stampa warned:

There is a danger that the information process will re-form around those who control the electronic media today, and not around the information specialists, the publishers and journalists… We must stand up to the theory of concentrated control if we want the medium to serve society and not vice versa.

Consolidated ownership and rapid technological transformations also demanded vigilance from journalists to safeguard quality.

We must take care that the new technology and the new politics do not combine to produce an age of new barbarisms, where rich men win the freedom to destroy the traditions of public service broadcasting, in favour of profitable rubbish, while writers, musicians, and serious journalists are gagged to please a minority of bigots.

Media sans frontières (I)

Cable and satellite technologies were the first means for cross-border transmission, a marked departure from the earlier “point-to-point” technologies that had been so convenient for governments, post and telegraph offices, and censors.

For many, the promise of unrestricted cross-border communications offered the possibility of doing away with old information inequalities and even political structures. The first pan-Arab TV network, for example, was promoted as a tool to help eradicate illiteracy, since, according to its founder, no Arab government was willing to invest in the necessary infrastructure. The solution was to offer a package of programmes accessible to “all Arab states from puritanical, conservative Saudi Arabia, to liberal, sophisticated Tunisia” (IPI Report, March 1985).

IPI Report graphic illustrating the trajectory of the Soviet Sputnik satellite, October 1959

IPI Report graphic illustrating the trajectory of the Soviet Sputnik satellite, October 1959

A satellite makes its circular path in concert with the Earth’s rotation creating the practical illusion that it is stationary in the sky. From its lofty vantage point it cares not about the man-made boundaries on earth. Nor does it fathom the intricacies of having to deal with one Post Office or the other.

— Keith Fuller, ‘The Impact of Satellites’, IPI Report, November 1983

IPI Report cartoon depicting broadcast, June 1952

IPI Report cartoon depicting broadcast, June 1952

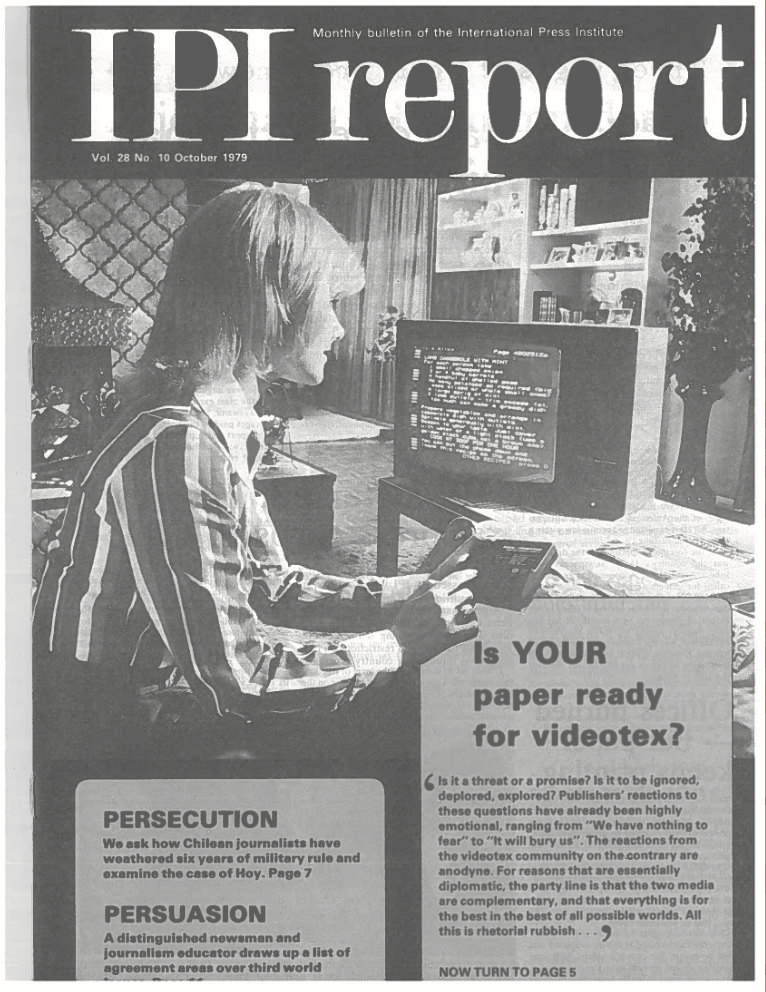

IPI Report 1979

IPI Report 1979

Media sans frontières (II)

Meanwhile, radio was also making a comeback, keeping channels open between East and West, North and South. Media entrepreneurs embraced radio’s lack of frontiers — a quality that posed problems for both dictatorships and democracies. Official and clandestine stations alike broadcast news, political messaging, and the latest hits.

It is a striking sight on the streets of Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, to see the local with his ear glued to his transistor, which, as often as not, he won in the local lottery. The other side of the coin is that radios have become one of the privileged targets of repression. Those carrying sets are often singled out by the military during demonstrations.

— ‘Aquino Closes Radio Stations’, IPI Report, October 1987

Governments jammed radio stations even as individuals hacked receivers. IPI Report covered the airwave propaganda battles between the United States and Cuba, rumours of Soviet technicians secretly adjusting domestic radio receivers in their spare time, and the British Home Office’s losing battle against pirate stations — one of which competed with Radio Moscow for a medium-wave frequency. These stations were the “newspapers of the air”, which “come and go like a magic roundabout [that] makes it very difficult to police”, one journalist wrote.

The Radio Free Europe transmitter in Salvaterra de Magos, Portugal, 1958. Fortepan

The Radio Free Europe transmitter in Salvaterra de Magos, Portugal, 1958. Fortepan

Revolutions on all channels

Hungarian and Soviet cosmonauts on TV, 1980. Fortepan / MHSZ

Hungarian and Soviet cosmonauts on TV, 1980. Fortepan / MHSZ

Images of the fall of the communist regimes were broadcast around the world: Censors and borders were no longer relevant. In 1990, ABC News asked Polish trade union leader Lech Wałęsa how democracy had come to Poland. He pointed to a television monitor and replied: “That’s how.” Pierre Salinger recalled this in “Private Television Has Played a Fundamental Role in East European Revolutions” (IPI Report, June/July 1990). Others were ambivalent about the new medium.

The recent events in Central and Eastern Europe have confirmed the power of the television image, its brutality at times, as well as its speed. This image has also revealed its limits and its weaknesses. They cannot be a substitute for the journalist capable of analysing facts with knowledge, experience and, above all, with critical reasoning, even if this costs a few moments’ delay.

Four decades after IPI first began critically examining the form and content of quality journalism, major post-war regimes collapsed once again — creating fresh opportunities to get to the heart of the story and continue scrutinizing the roles of both old and new media in the struggles and conflicts to come.

Credits

Project managers: Grace Linczer, Gabriela Manuli

Archival researcher, curator: Gwen Jones

Designer (in-person exhibition): Dinara Satbayeva

Logistics: Christiane Klint, Milica Miletić

Archival assistants: Mark Hatfaludi, Veronica Linczer

Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano

We are grateful to the following colleagues for their expertise and support: Ernst Arbouw, Renata Ávila, Amy Brouillette, József Bóné, Romina Colman, Scott Griffen, Julian Hatwell, Ada Homolova, Irving Huerta, Timothy Large, Jessica Ní Mhainín, Bob Stein, Csaba Szilágyi, Katalin Székely, Damla Tarhan Durmuș and Jenifer Whitten-Woodring. All images in this exhibition were first published by IPI unless stated otherwise. If you know the identity of any of the cartoonists or photographers, please let us know and we will credit them.

This exhibition is a first step in preserving and opening up the IPI historical archive, and these panels present just a glimpse into our materials. Our aim is to make this unique resource available to the public in digital form for inspiration as well as research: learning from, reconstructing, and deconstructing the history of the fight for press freedom and independent journalism.

An in-person version of this exhibition was presented at the 75th IPI Anniversary World Congress and Media Innovation Festival in Vienna (October 23-25, 2025).

Photo: Ronja Koskinen (IPI)

Photo: Ronja Koskinen (IPI)

To learn more about the archive, host our exhibition or learn more about our broader digitization initiative, get in touch with our team at archive@ipi.media